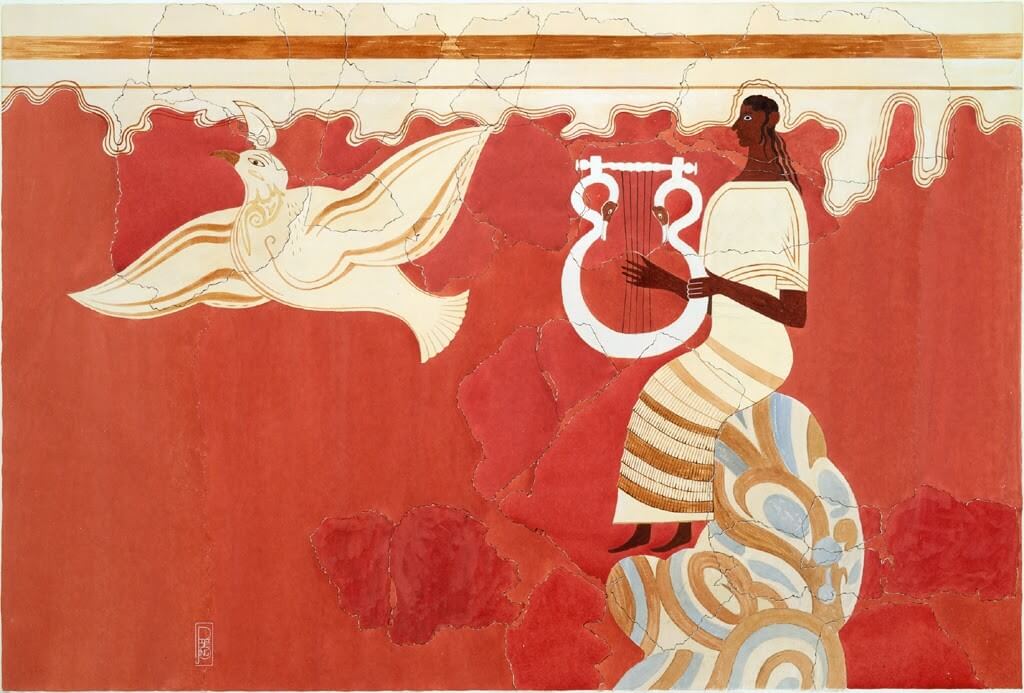

Although they are today read in books containing a stable and established text, the world’s great epics, be it the Iliad and Odyssey in Greek, the Rāmāyaṇa and Mahābhārata in Sanskrit or Beowulf in Old English, all originated in the ephemeral song of bards trained in the art of oral verse composition. The term oral verse composition means that the moment of performance is also the moment of composition. These great poems did not have a tangible form, they could not be opened or closed at will, stored in a shelf or leafed through from chapter to chapter looking for the right passage, but only existed as metrically arranged syllables, laced with the shimmering threads of the lyre’s golden twang, floating through the scented air of the halls of kings and nobles able to afford such high quality entertainment. Just as a gust of wind they would arise, summoned out of nothing by the magic of the bard, and then, dying down to a breeze, vanish into the surrounding air once the last syllable’s echo had rippled away along the walls. These bards did not reproduce poems they had memorised word for word and line for line, just as we maybe once were asked to do at school. As unbelievable as this might sound to all of those who had to go through the trial of memorising a poem: these bards were improvisers! Following an established story-line they would make up their lines on the spot, and maybe elaborate the story or shorten it according to the pay they could expect from their patrons.

To achieve this incredible feat of improvising in song what to us are timeless classics of literature, these bards used a traditional technique of composition based on metrical formulas. Conventional elements of storytelling, such as various details of battle scenes or arming scenes, the different stages in the reception of a guest or the rigging of a ship, down to simple things such as a character’s moving from one place to another, were all embedded into flexible formulas making up one or other part of a line, often containing a host of metrically identical and mutually replaceable elements. These formulas were the basic building blocks of any oral epic and the skill with which a poet did combine and recombine them, would to a large extent determine the quality of the resulting unique but traditional poem. Due to the constant need to introduce new speakers into the narrative or to make one character answer another character, all epic traditions have a network of formulas designed to help the bard to fulfil this basic need of storytelling. Below are a few examples drawn from Sanskrit, ancient Greek, Old English and Old High German. The most consistent in their use are the Greek and Germanic epic traditions, that is why they are here treated first.

Ancient Greek: The Homeric poems contain a celebrated formular line, in which the speaker is said to “speak winged” words in answer to another character.

καί μιν φωνήσας ἔπεα πτερόεντα προσηύδα· And, addressing him, he spoke winged words.

The identical or a similar line turns up 67 times in the Iliad and 64 times in the Odyssey. It is part of the beauty of traditional oral formulaic poetry that, once the perfect way of saying something had been worked out by generations of bards, no one in the audience would object to this kind of repetitiveness.

In the above type of formula the speaker is not named. There is another type in which the character’s name always appears in the second part of the line accompanied by an epithet.

τὸν δ’ ἀπαμειβόμενος προσέφη πόδας ὠκὺς Ἀχιλλεύς· To him in answer spoke swift-footed Achilles.

τὸν δ’ ἀπαμειβόμενος προσέφη κρείων Ἀγαμέμνων· To him in answer spoke the ruler Agamemnon.

τὴν δ’ ἀπαμειβόμενος προσέφη νεφεληγερέτα Ζεύς· To her in answer spoke cloud-gathering Zeus.

All these lines are exactly parallel in their metrical and grammatical structure: they open with an accusative pronoun indicating the one spoken to, followed by a participle meaning “answering” and a verb meaning “spoke”. The line is in each case finished by a combination of epithet and personal name. The refinement of this system, designed to make basic tasks of storytelling easier for the bard, appears once one realises that all the epithet and noun combinations are metrically equivalent and therefore freely interchangeable.

Old English: The typical way of introducing a new speaker into the narration of traditional Germanic poetry is very similar to the one discussed just above. The verb for “speak” with the name of the character as its subject is combined with a parallel subject (a word such as son, king or protector further defining who the character is) followed by a noun in the genitive, indicating that the character in question is the son of someone or the king of some land.

Hroðgar maþelode, helm Scyldinga – Hrothgar spoke, protector of the Shyldings (the Danes).

Beowulf maþelode, bearn Ecgþeowes – Beowulf spoke, son of Ecgtheow.

Old High German: In the epic fragment of the Hildebrandslied the Old High German equivalent of the exactly same formula is used.

Hiltibrant gimahlata, Heribrantes sunu – Hildebrand spoke, son of Heribrand.

Sanskrit: The system used by traditional Indian epic is less clearly structured and more flexible, but it too contains repeated formular elements used to open speeches. Consider the following examples.

नेत्राभ्यामश्रुपूर्णाभ्यां सुमन्त्रमिदमब्रवीत् Both eyes filled with tears, he said this to Sumantra.

शोकोपहतया वाचा कैकेयीमिदमब्रवीत् With a grief-stricken voice he said this to Kaikeyi.

गन्धर्वराजप्रतिमं भर्तारमिदमब्रवीत् To the husband, looking like the king of the Gandharvas, she said this.

Note how the verb अब्रवीत् (abravīt), he/ she said, remains in final position in all three examples. In each instance the verb is preceded by the accusative demonstrative इदम् (idam), this. The space between these two words and the medial caesura is in each example taken up by the accusative of the name of the character spoken to. The first half-line is taken up by a freely chosen element suiting the context of each line.

Silvio Zinsstag,

teacher for ancient languages

Hi

Do you have the Iliad translated as per illustrated on youtube?

Full https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qI0mkt6Z3I0&t=389s

Hi Sean apologies for this late reply your comment was missed! We don’t have a translation done however there are many reputable translations available.