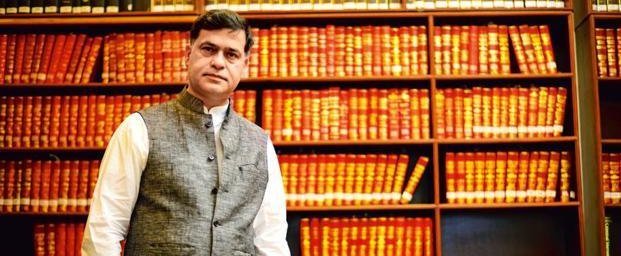

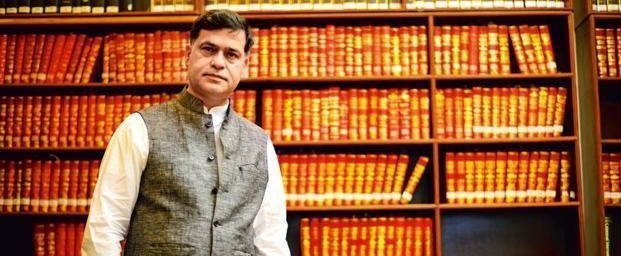

Under the garb of a lawyer par excellence lies a heart that beats for the composite culture of India and its literary and cultural traditions.

Mr Luthra’s grandfather Mr Malik Hansraj Luthra

Mr Luthra’s father’s and mother’s family moved to India from West Punjab after the partition in 1947 and his grandfather was alloted agricultural land in Indian Punjab after a few years. “We speak Punjabi at home, but our spoken dialect is different from the Punjabi of Eastern Punjab”, he remarks while talking about his family’s journey to post-partition India, “My grandfather would write to his staff on our farm in Bhatinda (now Mansa) in Punjabi but in the Shahmukhi script. And my father used to make his case notes in Urdu or English. I still have his old registers with his notes in Urdu”, he adds.

Ever since childhood, Mr. Luthra has seen Urdu used for work and for personal communication in his family. And while his own use of Urdu was limited he greatly desired to learn the script that both his grandfather and father had mastered. “I bought a book to learn the Urdu script when I was in college”, he recalls, “but my attempts didn’t work”. Nastaliq, the script for writing Urdu, is indeed a complicated writing system. It does not promptly divulge its secrets to learners.

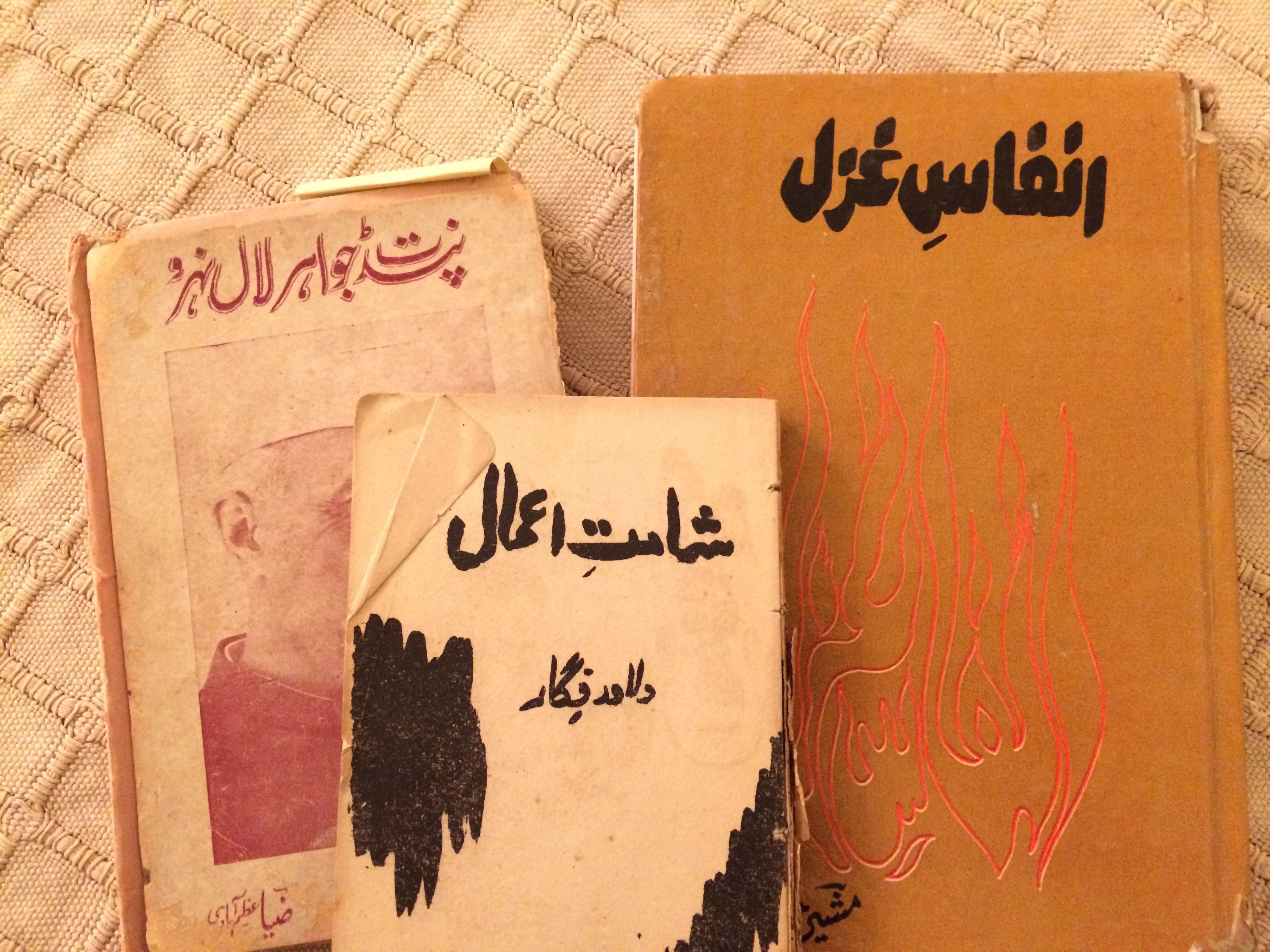

Many of his friends were intrigued by this commitment to learning Urdu given his hectic work schedule. He was at that time Additional Solicitor General of India at the Supreme Court. “For me, it was a good opportunity to connect with my family’s heritage”, he says. When the senior Mr. Luthra was alive, mushairas (poetry-meets) and Indian classical musical performances were commonplace at their home. He recalls, “My father had a phenomenal memory and was very fond of literature, he could quote Shakespeare by heart and also knew a large number of couplets in Urdu and in Persian. He was particularily interested in Urdu and Persian poetry and literature – I still have few of his books.”

He also wants to learnt Sanskrit one day. As an Arya Samaj follower, he already recites Sanskrit mantras with ease and hopes to master the language someday soon. As he comes from a family of polyglots, and himself speaks Hindi, Punjabi, Urdu, English and (passable) French, it will not be surprising when one day he fulfils his dream of learning Persian and Sanskrit as well.

Talking about the origin of Urdu Mr Luthra says, “Urdu was born because there was a need for a common medium of communication between different sections of the population and those who governed the society and were in charge of administration.” For someone who has witnessed the process of assimilation first hand, it is almost intuitive to see how the migration of people and their languages leads to the creation of new ones.

It is also no surprise then that Mr. Luthra has encountered the Urdu language not just in high literature and music, but also in several legal records from pre- and post-partition that pertain to common people. Recounting his exhilaration at reading these records Mr. Luthra says, “The satisfaction of reading them in the original is unmatched.”

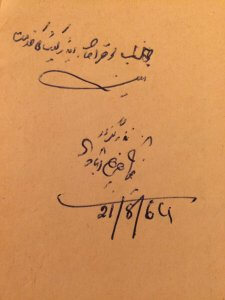

Mr K K Luthra’s handwriting

Other Hindi speakers who learn Urdu also go through a similar experience. The text written in Urdu, barring a few words, is almost fully comprehensible to them. The only tricky part is decoding the script. Mr. Luthra believes that once Hindi speakers master the script, learning Urdu will come easily to them. Based on his own experience, he comments, “Hindi speakers can easily contextualise new Urdu words. The only real challenge is not lapsing into the tendency of using Hindi words in Urdu, and instead continuously work towards on building a strong Urdu vocabulary.”

Yet despite the efforts of intellectuals, students and heritage speakers like Mr. Luthra who are trying to revive their centuries-old connection to Urdu, the great poetic and literary traditions of the language are slowly becoming obsolete in modern India as the country is reinventing itself in the 21st century. Mr. Luthra feels that we are at risk of losing this part of our heritage as the generation fluent in Urdu is passing away. An observation that echoes the feelings of admirers of Urdu today.

Many people now commonly think of Urdu as a language belonging to the Muslim community, a historically inaccurate assumption that Mr. Luthra dismisses outright. He explains, “The spoken language in north India was Hindustani which was a mixed language. Apart from Central India and Hyderabad, the Muslims in southern and eastern Indian states speak, read and write their own regional languages – Urdu is not their spoken or written language, thus treating Urdu as relatable to the Muslim community alone is unwarranted.”

Today many of us struggle with the differences and apparent contradictions between the many languages and cultures in India, but Mr. Luthra has turned this rich cultural heritage into one of his key strengths. Being multilingual comes naturally to him; he can easily switch from Hindi to Punjabi to Urdu to English and then back to Hindi in any conversation depending on the comfort of the person he is speaking to. Through his magnetic persona and his extensive scholarship, he inspires us to emulate his example and rediscover our heritage with an open mind and heart.

Read more by Zabaan:

Mr izhaar asar is my maternal grandfather and i m proud of him

We must connect then

Luthra Sahib, Punjab is always ahead in Hindustan. So proud to be Punjabi.

Urdu is a language with beautiful expressions which developed in the sub-continent and is, unfortunately, being sidelined.