In this article Neha Tiwari looks at the theory of Rasas in Indian Arts in the context of Kālidāsa’slyric poem Meghadūt.

Life is nought without emotions. The famous French philosopher Descartes famously said, “I think therefore I am”. But after reading the lyric poem, Meghadūt, I feel that author Kālidāsa—albeit a predecessor of Descartes by several centuries—would have countered him by saying, “I feel therefore I am”.

Depiction and evocation of various emotions have been studied extensively in Indian aesthetics, especially in the fields of literature and dramaturgy, for many centuries. One of the earliest available works in the field is Nātya Shāstra by Bharat Muni, believed to have been written between 200 BC and 200 AD, which delves into the theory of rasas and the purpose of art in our lives.

Rasa, or essence, is a concept in Indian arts described as the soul of any verse. Indeed, Rasa is the aesthetic essence of a work, one that evokes an emotional response that helps the audience step out of the conventional bounds of time and space and connect with something or someone outside themselves, be it through the depiction of love or war. Rasa is what moves us at an emotional level and churns the very engines of pleasure and pain in our minds, and in doing so helps us experience both transcendental joy and agony.

Bharat Muni categorized the rasas into eight major types that broadly cover feelings of love, humour, disgust, anger, valour, compassion, horror and amazement. The Love Rasa, or Shringār Rasa, is that which evokes a sense of longing for a divine union. As the word Shringār suggests, this type of rasa titillates us, makes us love, and long for love in return. Bharat Muni further divides Shringār Rasa into two types: Sanyog, meaning union, is the feeling of love that arises from being with one’s lover; and Viyog or Vipralambha, meaning separation, is the feeling of longing lovers feel when they are apart.

Kālidāsa—one of the greatest Sanskrit poets of ancient India—was a master at evoking the Shringār Rasa. His lyric poem Meghadūt, or Cloud Messenger, is a verse about a divine being known as a yaksha who has been separated from his wife and requests a cloud to deliver a message to her.

Kubera, the king of yakshas (Source: Wikipedia)

Although yakshas can take any form and can travel at lightning speeds, the yaksha in Meghadūt has been stripped of his supernatural powers and separated from his wife by his master who cursed him for dereliction of his duties. Now sitting lonely at an ashram in the Ramgiri mountains, the forlorn yaksha is left missing his wife and becoming frail thinking about her constantly. This sets the stage for the unfolding of the Pravāsa Shringār Rasa, a type of Viyog Shringār Rasa experienced during prolonged separation from a loved one.

As the yaksha tries to convince the Cloud to take the journey to where his wife is, he promises a path full of adventure and reunion for the Cloud itself. The yaksha tells the Cloud that during its journey it will come across the river Nirvindhya, which he visualises as the Cloud’s lover who has become frail, longing for her reunion with the Cloud in the form of rain, a fate all too familiar to the yaksha.

The yaksha then speaks of the joyful welcome the Cloud will receive from his friends, the peacocks, and the goodwill of the Gods that the Cloud will earn while passing through Ujjain when the sound of his thunder will serve as drums in the worship of Lord Shiva. Mindful of the needs of the women there who come out at night to go to their lovers but find themselves engulfed in darkness, the yaksha asks the Cloud to shine in the night while being careful not to scare the women with his thundering voice.

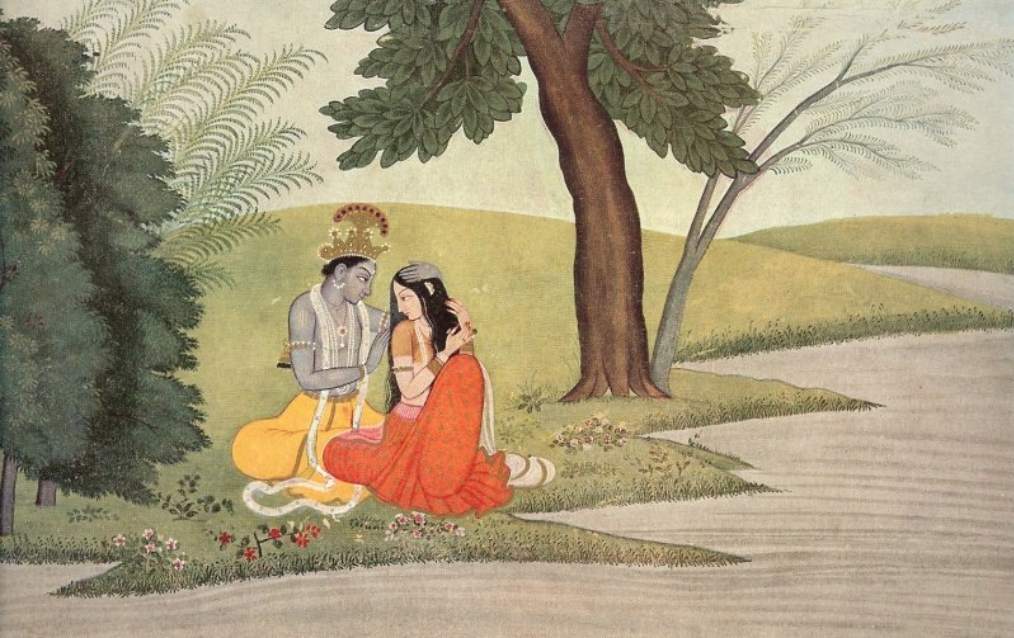

Yaksha’s wife with the Cloud (Source: Tribune India)

The yaksha also offers instructions for when the Cloud finally reaches his home. The yaksha asks the Cloud not to interrupt his wife’s sleep when it arrives so as not to rob her of her dreams. He knows his wife may be able pass the daytime engrossed in daily chores, but will find their separation unbearable at night when she cries herself to sleep in hopes of reuniting with her husband in her dreams. When she wakes, however the Cloud is to deliver his message, a token of love for her:

“I see your body in that of the delicate Priyāngu creeper, your eyes in that of a timid doe, your beauty in the moon, your hair in the lustrous feathers of a peacock and your eyebrows in this slender riverstream. But none of these things match up to you. I am suffering without you.”.

He hopes that his message will augment her feelings of love for him, so that even in this period of separation, their love for each other does not diminish.

Praising the Cloud for his kindheartedness as it sets out for the journey, the yaksha describes the Cloud as the one who urges tired travellers to return home with its serious yet sweet thunders. The yaksha expresses immense gratitude to the Cloud for undertaking this journey along with his wish that the Cloud never meet the same fate of being separated from his wife, Lightning.

Meghadūt clearly illustrates that for a poet with immense sensibilities like Kālidāsa, love is not the exclusive preserve of humans. The yaksha in Meghadūt is intensely receptive to nature and to all expressions of love in nature. For Kālidāsa, the feeling and expression of love in union and separation is seen in creatures other than humans and in elements of nature too. Today, as linguists are beginning to decipher the language of bats and other animals, and scientists are beginning to unearth the secret communications between trees via their roots, a poet of Kālidāsa’s skill and stature writing 1500 years ago can be forgiven this anthropomorphism.

In fact, by making the expression of love universal, Kālidāsa sets before us an unmatched ideal of sensitivity and receptiveness. He looks at the world with a gaze full of love, and everywhere his love-laden gaze falls, it becomes imbued with love, beauty, and emotion. He is intimately aware of what transpires between lovers, how they tire after their union, how the soft breeze coming from the nearby river reinvigorates their spirits, and how even after being separated their hearts and minds stay together. For Kālidāsa, the whole cosmos is a symphony of love, of the lovers’ fervid unions, and of impassioned separations witnessed everywhere and in everything around us.

Could love be one of the divine laws of nature? If so, the rasas of Sanyog and Viyog are surely psychological manifestations of laws that govern the entire universe and all the creatures and elements in it.

Radha and Krishna, Pahari Painting (Source: Nickyskye Meanderings)

Countless couplets, verses, and songs have been written in India on the themes of love explored by Kālidāsa and the great poets who came before and after him. The Indian sensibility has been nourished by this imperishable fountain of love for two thousand years or more—whether it be the pain of the traumatic separation of the Krauncha birds that inspired the first poet-saint Valmiki to compose Rāmāyan, the rich verses of Kālidāsa that powerfully evoke the Shringār Rasa, Meera’s love and devotion that inspired her songs to Lord Krishna, or the muse of the proverbial āshiqs of Urdu ghazals. It seems that love is destined to persist as a cherished theme in Indian aesthetics, art, culture, literature, music, and now films for generations to come.

Read more by Zabaan:

You have rightly made mention of the poetic genius of mahakavi kalidas, Meera and various authors of Urdu Gazals but seem to have forgotten the work in Tamil of Sri Andal who portrays through her divine work,”Nachiyaar thirumoli” divine romanticism between her (the soul) and KRISHNA (the divine incarnate).

You are right in mentioning Andal whose love for Krishna and which is expressed by her in her beautiful melodious poems are unique but they don’t have linguistic grandeur of Kalidas.

Very true sir it’s an epic from one who is considered god in human form