In this blog Srotoswini delves into the idiosyncracies of Hindi as spoken in Mumbai!

“…ye saala men log, humesha humari vaat laga deta hai!, ” – a woman, complaining about her daily life at work.

“…arey bantai, mai kabse idharich khada hai. Tereko time pe aane ka na bhau!” – a Mumbai local youth, waiting for his friend at Govandi railway station.

Anyone who has lived and loved Mumbai can confirm that it is the prototypical cultural salad bowl to the anthropological enthusiast.

It includes the sleepy, professional 9 to 5-er vibe that is in Northern Mumbai, where the most common forms of speech are an arduously decolonized Hinglish and the Gujarati lingual area of Ghatkopar.

It also includes the fashionable and uber-cosmopolitan So-Bo, where the rich and the filmy lead their innocuous lives, mingling amongst one another in a peculiar Parsi-influenced English or Hindi.

It is neither completely constructed by the dockworkers and fishermen of Mazgaon whose linguistic heritage draws vocabulary from Marathi, Hindi, Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam and English; nor is it wholly occupied by the migrant slum-dwellers, daily wage workers and labelled outlaws of Dharavi and Kamathipura, whose spoken language imbibe many words and grammatical configurations from their native tongues from all over India.

It is also not entirely shadowed under the lazy suburbs of Chembur and the crime hotspots of Govandi and Wadala.

Talking about Bambaiyya Hindi (Mumbai’s Hindi) in an all-encompassing manner would be to run the generalised paint brush over its fascinating multiplicity. So I’ll try to limit my observations to the peculiar Hindi that is spoken in central Mumbai.

In the following paragraphs, I try to look at it through the eyes of a language-lover, breaking down and negotiating with some of its peculiar vocabulary and transient grammar. This is nowhere close to a thorough analysis but is only an attempt at scratching the surface of an extremely emotive and rich linguistic heritage.

Understanding the Self and the Other

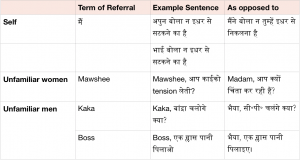

Learning to use any language conversationally means mastering the first and second person, most of all and learning the local terms of reference for unfamiliar people. In Bambaiyya Hindi, the personal pronoun मैं or अपुन (I) is used to denote self.

However, using the third person for the self is possible to indicate a gangster-like self-important quality to the speaker, normally with the word भाई (brother). As in standardised Hindi, there are three forms of you – आप (formal), तुम (informal, casual) and तू (intimate).

If one were to carefully observe spoken patterns in Bombay, it may become evident that the more widely used pronouns are आप and तू. Whether this suggests a definitive nature of social contact in Mumbai, where one is either distant or very intimate, is upto the user of the language, but is interesting in the light of Bombay’s unique social composition.

Another beautifully intimate quality of Bambaiyya Hindi is the close proximity and respectful seniority it imparts to terms used for unfamiliar people. It is considered appropriate to refer to an unfamiliar older woman as “mawshee,” Marathi for maternal aunt; and unfamiliar men as “kaka”, Marathi for father’s older brother. Other characteristic forms include, “bhau,” Marathi for brother and the English word “boss,” meanings intact.

Oblique Pronouns

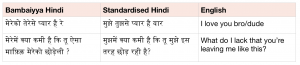

In Bambaiyya Hindi, the oblique forms of the pronouns (मुझ and तुझ) are not commonly used and are replaced by the possessive forms.

Obligation and Compulsion

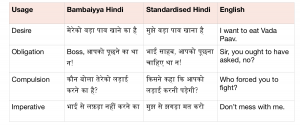

Hindi often uses the infinitive form of the verb in the construction [(subject) को infinitive होना], which translates into [X has to (verb)]. Bambaiyya Hindi simplifies matters somewhat for its speakers because the oblique infinitive in conjunction with का performs many roles.

It can act as an obligation, external or self-driven compulsion, desire as well as an imperative construction.

However, it is worthwhile to note that the imperative in such a construction almost always has a tone of impending danger or threat, without which the conjugation reverts back to the tamer versions of आप करो (कीजिए is rare) and तू कर.

Moreover, using this construction to express desire is strengthened further by the addition of the verb माँगना (to ask for, to demand). For instance, “मेरेको समोसा खाने को माँगता है” (Trans: It is ‘demanded’ that I eat a samosa) contains more emphasis and emotive quality than simply “मेरेको समोसा खाने का है” (Trans: I want to eat a samosa).

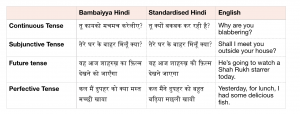

Deconstructing and Supplanting Tenses

The tenses take their own unique and extraordinary rendition in Bambaiyya Hindi, far removed from the structured forms in standardised Hindi.

The first thing I note, with relief, when I look at verbal constructions in Bambaiyya Hindi is the lack of the transitive-intransitive distinction in the perfective tense, which also assures that agreement is with the subject regardless of the quality of the verb.

Hindi grammar dictates that a perfective transitive verb must block its subject with the agentive post-position ने and agree with the object or the new grammatical subject in the sentence. In Bambaiyya Hindi, such complications are done away with quite casually with a victorious dropping of the ने. For instance, मैं तेरेको वह-इच बोली जो वो मेरेको बोला (I told you exactly what he told me) in place of मैंने आपको वही कहा जो उसने मुझसे कहा.

The continuous tense in Bambaiyya Hindi has a conjugation that is heartfelt. I say this because there is no sounder way to seem more tapori (gangster) than by using this construction. Instead of the elaborate three part construction in standardised Hindi, it uses the following condensed versions, which may have roots in Marathi:

मैं सो रहा हूँ : मैं सोरेलाए

वे सो रहे हैं : वो सोरेलेए

वह सो रही है : वो सोरेलीए

Finally, in standardised Hindi, the only times nasalisation is used in the future verbal constructions is with the first person and plural subjects. Bambaiyya Hindi nasalises everything but for the first person, where agreement is either masculine or feminine singular. Notice the difference in construction:

मैं खाऊँगी/खाऊँगा: मैं खाएगा/खाएगी

यह खाएगा : ये खाएँगा

ये खाएँगे : ये खाएँगे

Except तुम, which is irregular almost everywhere in most cases.

When in Mumbai/Bombay:

In this section, I’m going to put down a list of some extremely useful vocabulary and phrases that I wish somebody had introduced me to, when I had first moved to Bombay.

My baby steps in learning Bombay’s unusual lingo, verbal and non-verbal cues and gestures, had been comical and sometimes disastrous because I couldn’t comprehend or identify with most of it. I remember telling a guy off for making kissing noises at me in the railway station, only to discover much later that it’s only the most socially accepted gesture used in the place of “excuse me,” regardless of who is spoken to – man, woman or child.

This list is far from exhaustive, but suffices, I think, to have an upper hand on your first few weeks in Bombay.

Having engaged with some tenets of a vast and ever-evolving language such as this, you might want to go back to the beginning of this article and try to translate the two sentences that I started with, and perhaps use some of these constructions in your daily life to spice up your own Hindi.

The emphatic and sentimental quality of Bambaiyya Hindi holds true appeal due to its unique flavour. It sets itself apart from more sophisticated forms such as the Urdu tahzeeb of Uttar Pradesh and the Punjabi-tinted Hindi of Delhi.

The spice in Bambaiyya Hindi is one of informality and freedom, perhaps owing to the fast-paced way of life in Mumbai and the integration and retention of many languages within it. It contributes to my undying love for all things Bombay, here’s hoping you feel the same.

Photo Credit: India Tribune

Read more by Zabaan:

I just came across this blog while doing research for my term paper on sociolinguistics. So well written and loved how it’s been concluded without any usual snobbish remark on the essence of bambaiyya Hindi. Thanks for such informative and fun read!

Well written! Reached the ‘ root’ of the matter.

Informative. Based on the examples used, it sounds like the author was inspired by a Sacred Games binge.

Nice article Sroto! Well caught. My own experiences in Mumbai have made me familiar with most of these. I love the “Mereko” instead of “Mujhe”!!!

Well written. I enjoyed it thoroughly.